Declassified images from U.S. military satellites are helping find forgotten mine fields in Cambodia.

From the late 1960s almost until the end of the 1990s, a bloody war between communist groups and democracy defenders raged, with a few short breaks, in the jungles and on the rice fields of Cambodia. The conflict left behind a hidden legacy that keeps increasing the war's death toll to this day.

Over 10 million anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines and other explosives may have been scattered across Cambodia's land during the decades of fighting. Over half of them may still lurk in the ground, waiting for unlucky people or vehicles to set them off. Since the war's end in 1998, over 20,000 people have been killed and 45,000 injured in mine accidents in Cambodia. The toll is still rising.

"There were over 50 accidents last year," Tobias Hewitt, the country director for Cambodia at the HALO Trust, a de-mining non-governmental organization (NGO), told Space.com. "The number is steadily decreasing, but it's still a huge problem."

The HALO Trust has been working in Cambodia since the 1990s, helping to scour hundreds of square miles of contaminated land. The work is tedious, and progress is slow. It requires teams of technicians with mine detectors to comb the land square foot by square foot. The problem is, they don't always know where to look.

"During the Cambodian conflict, a lot of the information was never recorded," Hewitt said. "Mines were put there, people left and have forgotten about it."

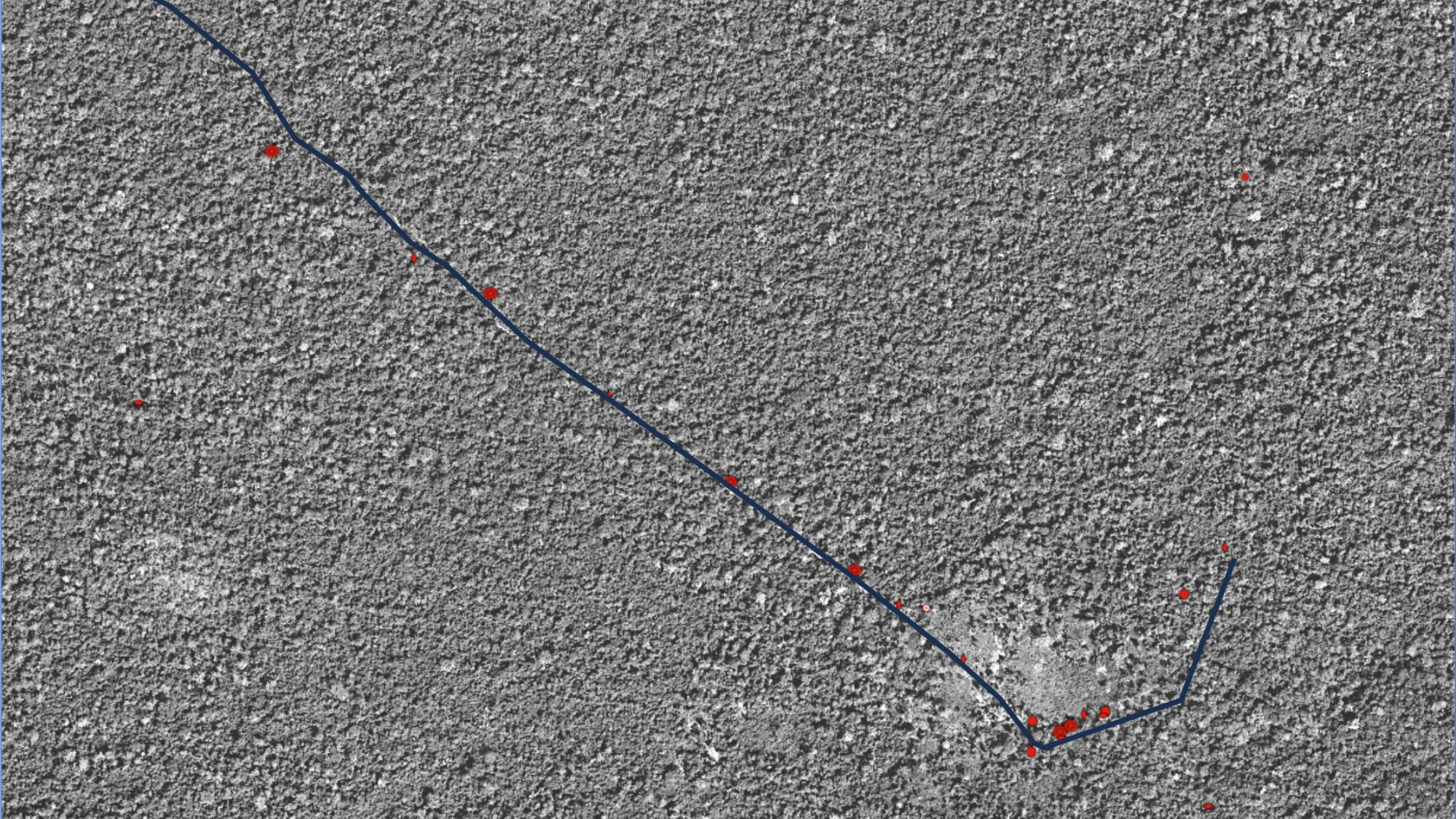

The HALO Trust team has been relying on satellite images for years to look for suspect areas. But the landscape has changed since the war's end. Jungle has grown, villages have been abandoned and roads have stopped being used. Last year, the de-miners decided to search for clues in images captured by U.S. military satellites in the 1970s and 1980s.

The images were captured by the HEXAGON fleet of satellites operated by the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office. The satellites used old-fashioned film to take their snaps. The film spools would be sent in sturdy return capsules to Earth, where the images would be developed. The data was kept secret for decades. But in 2011, nearly 30,000 images were declassified and made available to the public through the Department of State.

The HALO Trust team found thousands of images of regions in the west of Cambodia, where most of the suspected mine fields are located. It's been a game-changer.

"We were able to overlay those old images on regular Google Earth images and find old roads, for example," said Hewitt. "That's a huge help, because that's where most mines would be put in the ground. We would not be able to know about them otherwise."

Cambodian society has changed since the war. Many people have moved into cities. Those who lived through the conflict are dying. New farmers begin to work the land, oblivious to the hidden danger.

"If they don't know that there used to be a road, they just assume it's farmland and plough it," said Hewitt. "Unfortunately, accidents happen."

In recent years, as Cambodia's economy began to grow, farmers have started abandoning traditional manual farming methods and began purchasing tractors and other machinery. That, Hewitt said, opened up a new can of worms.

"There are two types of land mines in Cambodia," said Hewitt. "Anti-personnel mines, which only need a very small amount of pressure to explode, and anti-vehicle mines. The anti-vehicle mines may have been buried in the ground for decades. You can walk over them and nothing happens. But now, with the mechanization of agriculture, you are setting off those mines that have been dormant for decades."

The old military satellite images are helping to speed up the clearance. However, Hewitt, said that the process is still time-consuming and laborious.

"We have to manually sync those images with our existing maps and then go over them inch by inch looking for old roads," Hewitt said. "Then, once we have an area where we think there used to be a road, a team will go there and try to confirm that information through ground survey work."

In the few months since the project started, the HALO Trust team has analyzed all the suspected areas in western Cambodia and identified several high-priority areas where mines are likely present. With the vast amount of land remaining to be cleared, zooming in quickly on the most dangerous zones could save lives.

"You don't have the luxury to clear everything," said Hewitt. "You need to focus on the highest priority. With these additional assets and different information points, we can better prioritize what we are doing and do it in the most efficient way possible."

Since the 1990s, Cambodia has cleared about 1,200 square miles (3,100 square kilometers) of mine-contaminated land. According to estimates, some 180 square miles (470 square km) remains to be cleared. The country hopes to be rid of land mines completely by 2030.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments