Uranus just got a little more time on its hands.

A fresh analysis of a decade's worth of Hubble Space Telescope observations shows Uranus takes 17 hours, 14 minutes and 52 seconds to complete a full rotation — that's 28 seconds longer than the estimate provided by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft nearly four decades ago.

In January 1986, Voyager 2 became the first — and so far the only — spacecraft to explore Uranus, and with its data, astronomers pegged the ice giant's rotation period at 17 hours, 14 minutes and 24 seconds. This estimate was based on radio signals emitted by the pale turquoise planet's auroras and direct magnetic field measurements. This figure became the bedrock for calculating coordinates on the enigmatic world and mapping its surface. Scientists may need to rethink some of those maps, a new study suggests.

The initial estimate based on Voyager 2 data carried inherent uncertainties that led to a 180-degree error in Uranus' longitude, causing the orientation of its magnetic axis to become "completely lost" within just a couple of years after the spacecraft's flyby. Consequently, coordinate systems relying on the outdated rotation period quickly lost their reliability, according to the study.

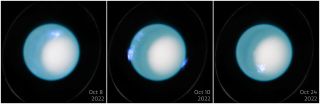

To resolve this issue, a team of astronomers led by Laurent Lamy of the Paris Observatory tracked the motion of Uranus's auroras using Hubble Space Telescope data collected between 2011 and 2022. By tracking the movement of these luminous displays over a little more than a decade, the researchers were able to precisely pinpoint the planet's magnetic poles and, in turn, a better estimate of its rotational period.

"The continuous observations from Hubble were crucial," Lamy added in a statement. "Without this wealth of data, it would have been impossible to detect the periodic signal with the level of accuracy we achieved."

This approach can now be used to determine the rotation rate of any celestial object with a magnetic field and auroras, not only in our solar system but also on exoplanets and other faraway worlds, the researchers say.

The updated estimate of Uranus' rotation period has provided a much more reliable coordinate system for the ice giant, one that is expected to remain accurate for decades until future missions can offer even more refined data, according to the new study. The improved estimate could also be useful in planning future missions to Uranus, particularly in defining orbital tours and selecting suitable atmospheric entry sites, Lamy and his team wrote in the new study.

This research is described in a paper published Monday (April 7) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments