Russia's war against Ukraine is waged not only with missiles and tanks, but with distorted myths — powerful narratives that romanticize empire, rewrite history, and embolden Russian soldiers to reduce once prosperous cities to rubble.

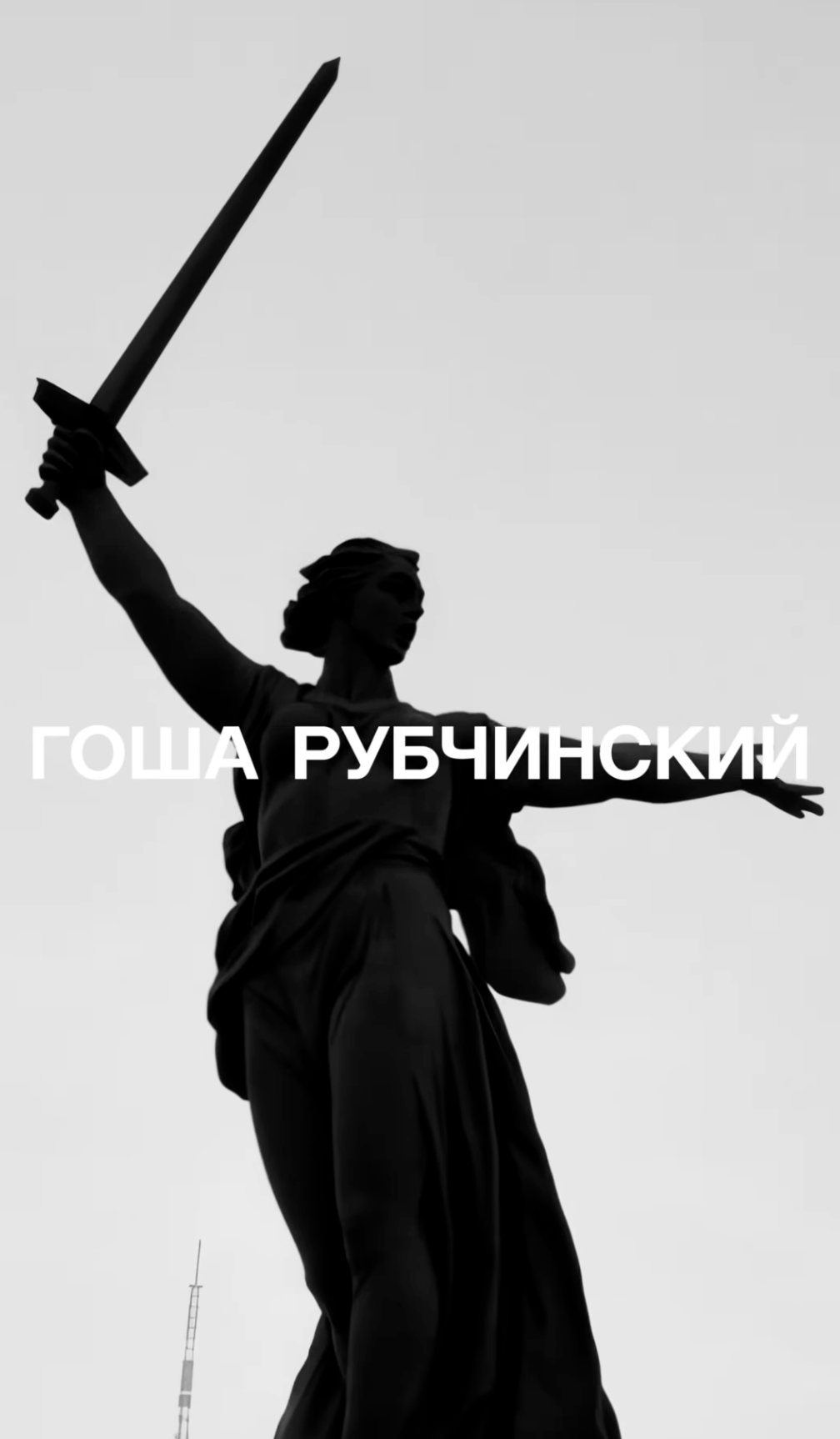

Those very same myths surfaced at the Photo London Festival from May 15 to 18, where the inclusion of Russian photographer and fashion designer Gosha Rubchinskiy's new book "Victory Day" sparked fierce backlash.

"The book is a non-partisan representation of post-Soviet military on Red Square," Rubchinskiy declared on May 14 in an Instagram post, adding that the photos "serve as a deeply personal representation of the individual outside of ideology and propaganda."

Though Rubchinskiy has long insisted that his work transcends politics, critics argue the photographer has been promoting pro-Russian propaganda through art and, in the case of "Victory Day," aestheticizing a war founded on violent falsehoods.

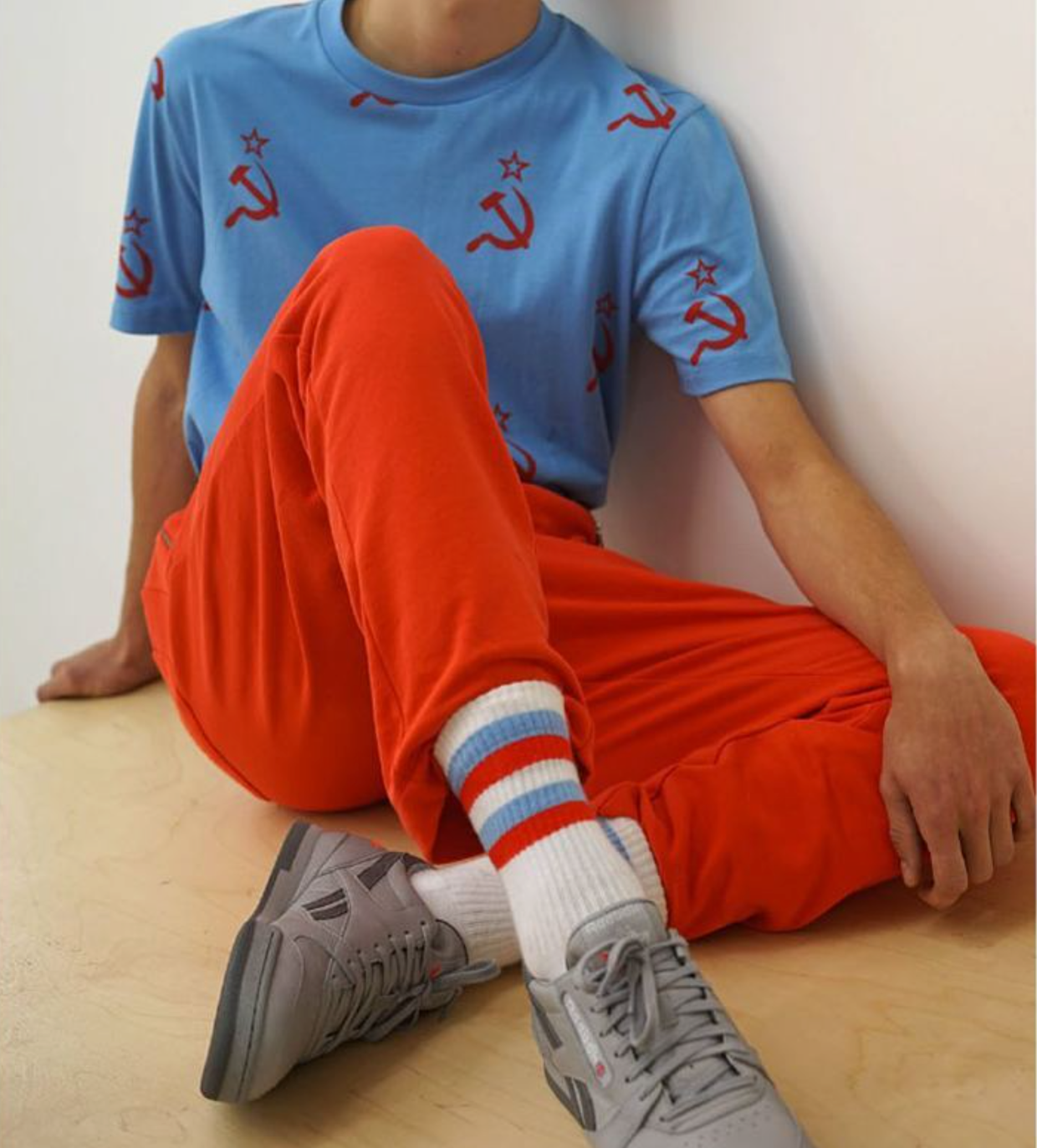

"His work extensively uses Soviet and Russian nationalistic symbols, which is problematic because they are currently used to justify war crimes, torture, and the killing of civilian Ukrainians," Emine Ziyatdinova, a Ukrainian photographer of Crimean Tatar descent, told the Kyiv Independent.

"As someone who is part of Russian society, it is nearly impossible (for Rubchinskiy) not to be aware of the semiotic connotations of these symbols and what they represent to the victims of these regimes."

Ideological military imagery

The black and white portraiture and "architectural studies" of Rubchinskiy's "Victory Day" were taken from 2018-2019, already half a decade into Russia's ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine.

Rubchinskiy invokes in the photo book's description potent military symbols like Red Square and the World War II memorial in Volgograd — sites that are meant to reinforce the Russian state narrative of the country’s military strength.

"For the last three years of the ongoing full-scale war in Ukraine, multiple Ukrainian cultural figures, curators, politicians, historians, scholars, and artists have tried to show Western cultural institutions that Russian culture is political and aligned with Russian imperialistic ideas."

In particular, Red Square is the location for Russia's largest Victory Day military parade, where during this year's commemoration, Russian President Vladimir Putin declared that Soviet soldiers "of different ethnic backgrounds… will forever remain Russian soldiers in world history."

Positioning the Allied Victory against the Nazis during World War II alongside the claim that it is somehow a book dedicated to "over 20 years of Russian youth culture," Rubchinskiy also appears to imply that this Soviet imagery can be claimed by Russians alone, and not the millions of Ukrainians, Belarusians, Kazakhs and other nationalities that fought and died serving in the Soviet army.

"Victory Day" was presented at the Photo London Festival by the exhibitor A/political, which says on its website that it prides itself on "producing radical knowledge through cultural terror."

"The presence of Gosha Rubchinskiy's work under the satirical title 'A/Political' at the London Photo Fair is yet another major disappointment and a clear example of the West's ongoing unwillingness to de-romanticize Russian aesthetics, which are rooted in military propaganda and oppression," Ukrainian photographer Daria Svertilova told the Kyiv Independent.

"For the last three years of the ongoing full-scale war in Ukraine, multiple Ukrainian cultural figures, curators, politicians, historians, scholars, and artists have tried to show Western cultural institutions that Russian culture is political and aligned with Russian imperialistic ideas. After three years of continuous horrors perpetrated by Russia in Ukraine, one would think these issues should be self-evident — but unfortunately, they are not."

Although "Victory Day" has yet to be widely released, an image displayed on Photo London's website depicts a young military conscript wearing the historic St. George Ribbon.

The black and orange ribbon has been a military decoration since the times of the Russian Empire and later came to be associated with comme— but these daysa symbol banned in Ukraine since 2017 due to its association with the ongoing full-scale war.

The Soviet army played an important role in defeating Nazi Germany, but during that time it was also responsible for a number of massacres, as well as deportations and forced relocations — atrocities that the Soviet government systematically attempted to cover up. Under Putin, Russia has distorted the history of World War II even further by using the accomplishments of the Soviet army as a means to "justify" Russia's war against Ukraine, who they depict as Nazis.

"The Russian state and society failed to recognize the war crimes and genocide the Soviet Union committed during World War II," Ziyatdinova explained.

"The glorification of these symbols in this exhibition normalizes them together with the past and current war crimes, instead of questioning what the Soviet Union and Russian state have done wrong."

At the time of this publication, neither the exhibitor A/political nor the Photo London Fair replied to the Kyiv Independent's request for comment.

Justifying annexation

"Victory Day" is not the first of Rubchinskiy’s projects since 2014 that blur the line between art and pro-Russian propaganda.

His 2014 book "Crimea/Kids" is a romanticized portrayal of youth in Ukraine's Crimean Peninsula. Promoting the book in the months leading up to Russia's illegal annexation, he was already speaking of the peninsula as Russian.

"All these kids were born in a new country, and because of the internet, they feel the same as other young people in London, China, or Japan. That's why it's interesting for me to see how these young kids born in an informational context manage to keep this kind of Russian spirit, this Russian view on things," he told German media outlet 032c in January 2014.

Speaking to British magazine Dazed in September 2014, already several months after the illegal annexation, he called Crimea's youth movement "a new Russia."

For natives of the Crimean peninsula like Ziyatdinova, who cannot return home as long as the Russian occupation continues, the depoliticization of the occupation — during which people have been not only forced from their homes but also arbitrarily jailed for opposing it — is especially painful.

It is wrong to publish a book on Crimea "with an emphasis on the Russian legacy on the peninsula, ignoring the ethnic persecutions, the military force and extensive propaganda used during the occupation," Ziyatdinova said.

"This book pretty much lies within the soft Russian propaganda claiming the newly occupied territories (as their own)."

Ideological slipperiness

Despite repeatedly claiming to be above politics, Rubchinskiy has occasionally let slip his belief that Russia suffers from biased media portrayal. In a 2018 article for British media outlet i-D, he lauded the World Cup for spotlighting Russia on the global stage.

"The World Cup is a unique reason to come to Russia and see what's going on here by your own eyes," he said. "Sometimes you should check for yourself and decide your own feelings about things rather than believe other people's opinion from the media."

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine also became a launchpad for Rubchinskiy's fashion collection Duval, which he tweeted about on Feb. 25, 2022 — just one day after the war began.

At this point — four years into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and the unlawful annexation of Crimea — Ukrainian political prisoners, including filmmaker and writer Oleh Sentsov, were already suffering harsh conditions in Russian detention, with Sentsov declaring a hunger strike to coincide with the international sporting event to demand the release of all Ukrainians imprisoned by Russia.

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine also became a launchpad for Rubchinskiy's fashion collection Duval, which he tweeted about on Feb. 25, 2022 — just one day after the full-scale war began.

His one-word tweet, "Duval," framed on the brand's website as "a statement of rebellion against the war," turned a tragedy for millions of Ukrainians into the Russian fashion designer's personal branding.

Such a move is part of the bigger issue which critics see with Rubchinskiy's work — namely, how it exploits post-Soviet trauma, repackaging collective pain as aesthetic currency.

"It is a space where pain, collapse, and violence experienced in the post-Soviet world are transformed into consumable images — rendered as aesthetic or nostalgic resources, easily instrumentalized," Ukrainian visual artist Yana Kononov explained in a post on Instagram on May 18.

"(Rubchinskiy's) work functions as a conduit for ideological slipperiness — capable of satisfying both authoritarian desire and Western taste for the 'critically charged'."

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thank you for reading this article. Here at the Kyiv Independent, we don’t put stories behind a paywall, because we believe the world needs to know the truth of Russia’s war. To fund our reporting, we rely on our community of over 18,000 members from around the world, most of whom give just $5 a month. We’re aiming to reach 20,000 soon — join our community and help us reach this goal.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  5 hours ago

1

5 hours ago

1

Comments