Today, Mars is a chilly desert of rock and dust — but 4 billion years ago, the planet had rivers, lakes and even oceans with sandy beaches. Data from China's Zhurong rover recently revealed the first evidence of one of those long-lost Mars beaches, finding shallow sandy slopes perfectly preserved about 33 feet (10 meters) beneath the Martian surface. Ground-penetrating radar aboard the rover measured thick layers of sand, sloping gently upward toward the rocky shore, as if washed up by ocean waves.

"The structures don't look like sand dunes. They don't look like an impact crater. They don't look like lava flows. That's when we started thinking about oceans," Michael Manga, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of earth and planetary science and co-author of the study, said in a statement. "The orientation of these features are parallel to what the old shoreline would have been. They have both the right orientation and the right slope to support the idea that there was an ocean for a long period of time to accumulate the sand-like beach."

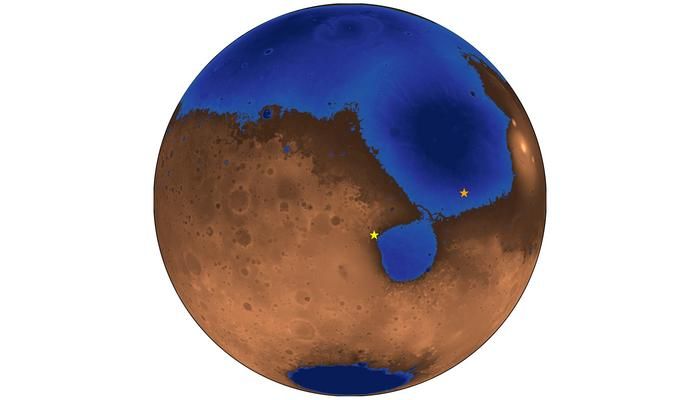

Zhurong spent a year, from May 2021 to May 2022, trundling along the base of a steeply-sloped rock outcrop at the edge of a wide, flat plain. From the rover's point of view on the ground, it's hard to tell, but this ancient shoreline on Mars seemed to lie inside a 2,050-mile-wide (3,300-kilometer-wide) impact crater called Utopia Basin. Utopia Basin is, in fact, the largest known crater in the entire solar system. Scientists had speculated Utopia Basin might once have held an ancient ocean, and they thought the escarpment overlooking Zhurong's route might once have been its shoreline.

And indeed, based on data from Zhurong, which researchers on Earth are still poring over, that speculation was right.

Along Zhurong's 1.2-mile (1.9-kilometer) route, its ground-penetrating radar beamed radio waves 262 feet (80 meters) down into the Martian ground. The way those radio waves reflected back to the instrument revealed underground features they came into contact with, like the boundaries between layers of rock and sediment. Thirty-three feet (10 meters) beneath the surface, the radar revealed smooth, gently-sloping layers of sand, several yards thick. Those layers appear to run parallel to the rocky cliff, and they rise toward that cliff at a shallow 15-degree slope — which is typical of beaches here on planet Earth.

The buried beach could represent the first evidence of a true ocean from Mars' ancient past, and its presence means the Red Planet must have had an ocean for millions of years — long enough to leave behind the thick layers of sand Zhurong's radar measured. And that ocean must have been fed by rivers, the scientists reason, as those rivers would have dumped sediment into the ocean. Waves would eventually have spread that resulting sediment along the shore, forming a beach that'd have been strikingly familiar to us.

"Shorelines are great locations to look for evidence of past life," Benjamin Cardenas, a geoscientist at Pennsylvania State University and co-author of the study, said in a statement. "It's thought that the earliest life on Earth began at locations like this, near the interface of air and shallow water." (It's not known exactly where or how life on Earth began, but shorelines like this one are a possibility, along with hydrothermal vents on the deep ocean floor.)

The discovery was a stroke of geological luck; Zhurong's beach would probably have eroded away into something unrecognizable over the last 3.5 billion years if it hadn't been buried beneath those 33 feet of rocky, dusty debris from asteroid impacts, volcanoes and dust storms.

"This strengthens the case for past habitability in this region on Mars," Hai Liu, a professor with the School of Civil Engineering and Transportation at Guangzhou University, a co-author of the study and a core member of the science team for the Tianwen-1 mission, which included China's first Mars rover, Zhurong, said in the statement.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments