U.S. President Donald Trump may follow the EU after all and impose more sanctions on Russia, already the world’s most sanctioned country, days after saying he wouldn’t.

Ukraine’s allies have imposed sanctions on Russia, as well as thousands of individuals and entities both in the country and around the world for aiding Moscow’s full-scale invasion. But there is still room for more sanctions to be introduced, experts told the Kyiv Independent.

While Russia’s economy hasn’t crashed and burned as some expected, the three years of sanctions are eroding the country’s fiscal stability, despite Moscow claiming otherwise. Russian GDP growth has dropped precipitously this year as sanctions hamper its main sources of income — oil and gas revenue — and curb imports of components needed for its military-industrial complex.

Sanctions on their own won’t end the war, but they are a crucial tool in the West’s efforts to pressure Putin to the negotiation table. Washington’s seesawing on its sanctions strategy has alarmed Brussels, but Europe and others remain united on the effort.

“All the other partners that we've been talking to, including Switzerland, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea, all think that Russia should be stopped with the help of the sanctions, and they're ready to do it,” Ukraine’s sanctions chief Vladyslav Vlasiuk told the Kyiv Independent.

“The EU has a lot of leverage in not just maintaining the sanctions pressure, but even increasing sanctions pressure,” he said.

Trump initially rejected joining the EU in further sanctioning Moscow for fear of derailing future trade and business opportunities with Russia, the New York Times reported on May 20. The previous week, Brussels said it was gearing up for a massive sanctions package after Russian President Vladimir Putin failed to attend peace talks in Istanbul on May 15.

Russia’s colossal three-day drone and missile campaign on May 23-26 appeared to change Trump’s mind. Speaking to reporters on May 25, he said he was considering sanctions after Putin had “gone absolutely crazy.”

Have sanctions against Russia worked?

Western sanctions have impeded Russia’s energy, financial, and military sectors, even if they haven’t stopped the war. Russia still has loopholes to get around sanctions, such as importing prohibited goods through Central Asia, but they are generally costly and time-consuming.

Ukraine and its allies have three key objectives when it comes to sanctions, according to Vlasiuk. To deny Russian state revenues, reduce its military capabilities, and undermine Putin’s regime.

The first two have yielded substantial results, with Russia losing $150 billion in oil revenues in three years due to energy sanctions and its military sector facing shortages in critical components, said Vlasiuk. The third hasn’t been successful as Putin still has widespread support from the Russian public, and that doesn’t look set to change, Vlasiuk added.

This year, Russia’s economy has started to contract for the first time since the start of the full-scale invasion in the first quarter of the year, shrinking by 0.4% compared to the previous quarter. In the same period, Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth saw a precipitous drop from 4.5% to just 1.4%.

While it’s hard to paint a fully accurate picture of Russia’s economy, due to the Kremlin restricting and manipulating data, Sussex University economics professor Richard Disney estimates that Russia’s economy is around 10% below what it would have been if it hadn’t invaded Ukraine.

"There's a shortage of workforce, there's the depletion of bank reserves, there's the collapse of certain investments. Foreign investment has dried up in Russia," Disney told the Kyiv Independent.

“The West is not willing to impose the sort of sanctions on Russia that would indeed be 'massive' because those sanctions would inevitably have a blowback on European economies and this would be weaponized by nationalist politicians.”

“Russia has gone from being close to a first-world country to heading in the direction of the third world,” he added.

Moscow has batted away claims that sanctions are impacting Russia, pointing to its economic growth over the last three years. In reality, it has divested spending from things like education and infrastructure towards the military.

This distorts actual GDP figures, and consumer spending and public investments have likely dropped by 15-20% compared to pre-war estimates, leaving Russians much poorer in reality, said Disney.

Western policymakers, particularly in Europe, have fed into Moscow’s propaganda by bigging up the impact of sanctions while holding back full force, said Tom Keatinge, director of the Center for Finance and Security at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a think tank. Instead, policymakers need to “manage expectations” on sanctions, he said.

The sanctions have also been imposed gradually over the three years instead of all at once, due to political hesitations and concerns about disruptions to global markets. While this gives governments time to fully prepare for the consequences of the sanctions, it means they are less effective.

“The West is not willing to impose the sort of sanctions on Russia that would indeed be 'massive' because those sanctions would inevitably have a blowback on European economies and this would be weaponized by nationalist politicians,” Keatinge said.

“The result is that Russia can adapt, shape-shift, and continue to gather the income and resources it needs to conduct its illegal war in Ukraine.”

Russia cuts key projects in aviation, tech, auto industries as oil revenues plummet

The Russian government is slashing budgets for major projects across a number of sectors amid an economic downturn and oil price collapse, the pro-Kremlin news outlet Kommersant reported.

Which sanctions have been effective?

Sanctions on Russia’s energy sector have often been criticized for being too loose, as Moscow exploits loopholes to export oil and gas and skirt the $60 oil price cap set by the West. Still, Russia’s fossil fuel sector continues to hemorrhage profits, and Europe has largely banned Russian energy, although it continues to import Russian liquid natural gas (LNG).

Russia earned around 242 billion euros ($275 billion) from fossil fuels last year, a 3% drop from 2023, according to the Helsinki-based Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). Sweeping sanctions at the start of the year helped tie up loose ends and targeted Russia’s opaque and uninsured shadow fleet, which carried 61% of its seaborne oil exports in 2024.

Once a vessel is sanctioned, ports will refuse to allow it to dock. In turn, Russia must spend more money finding new vessels to expand the fleet, piling up the costs and running down the profits.

"Selling oil through tankers is a lot more expensive than selling it through a pipeline,” said Disney.

Alongside energy sanctions, the West also went after Russia’s financial institutions at the start of the full-scale invasion. Most Russian banks, including its Central Bank, are barred from the Western financial world and cannot be used for trade or capital operations.

In 2022, Europe kicked major Russian banks off the SWIFT interbanking system, which pushed Moscow towards the Chinese banking system. But Chinese banks began limiting Russian transactions from December 2023 after Washington threatened to cut dollar access to institutions supporting Russia's military suppliers.

In November 2024, Washington imposed even more sanctions on 50 Russian banks, making transactions between China and Russia even more arduous. Moscow has repeatedly tried to lift financial sanctions and restore access to SWIFT, like in March, when it demanded a ceasefire in the Black Sea in return, which ultimately failed to materialize.

The West also froze some $300 billion in Russian Central Bank (CBR) assets at the start of the invasion, equating to around half of its foreign currency reserves. While there has been a hot debate about whether to mobilize these assets for Ukraine, simply taking so much money out of Russia’s reach was one of the most impactful sanctions, said Keatinge.

“Of course, this has been undermined by the Kremlin's ability to continue to raise foreign income via the sale of oil, so the effectiveness of the CBR asset freeze is reduced every day a Russian tanker is able to deliver oil,” he added.

In terms of tangible impact on the battlefield, Vlasiuk points towards the coalition of countries that prevents critical weapons components from entering Russia, known as the Common High Priority (CHP) item list. It covers everything from microelectronics to CNC machines and extends beyond Western nations to include countries like Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan.

“It imposes extra export controls over certain categories of products from the CHP list. And that makes it much more difficult for Russia to get those items imported,” Vlasiuk said.

Imports of these components are still flowing into Russia via third countries, largely in Asia. It is just harder to get them and more costly, leaving the Russian arms sector scrambling to find alternatives.

China denies Ukraine’s allegations of supplying arms, defense components to Russia

China’s reaction follows remarks by the head of Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service, Oleh Ivashchenko, about Beijing allegedly providing defense components to 20 Russian military-industrial manufacturing facilities.

What’s next?

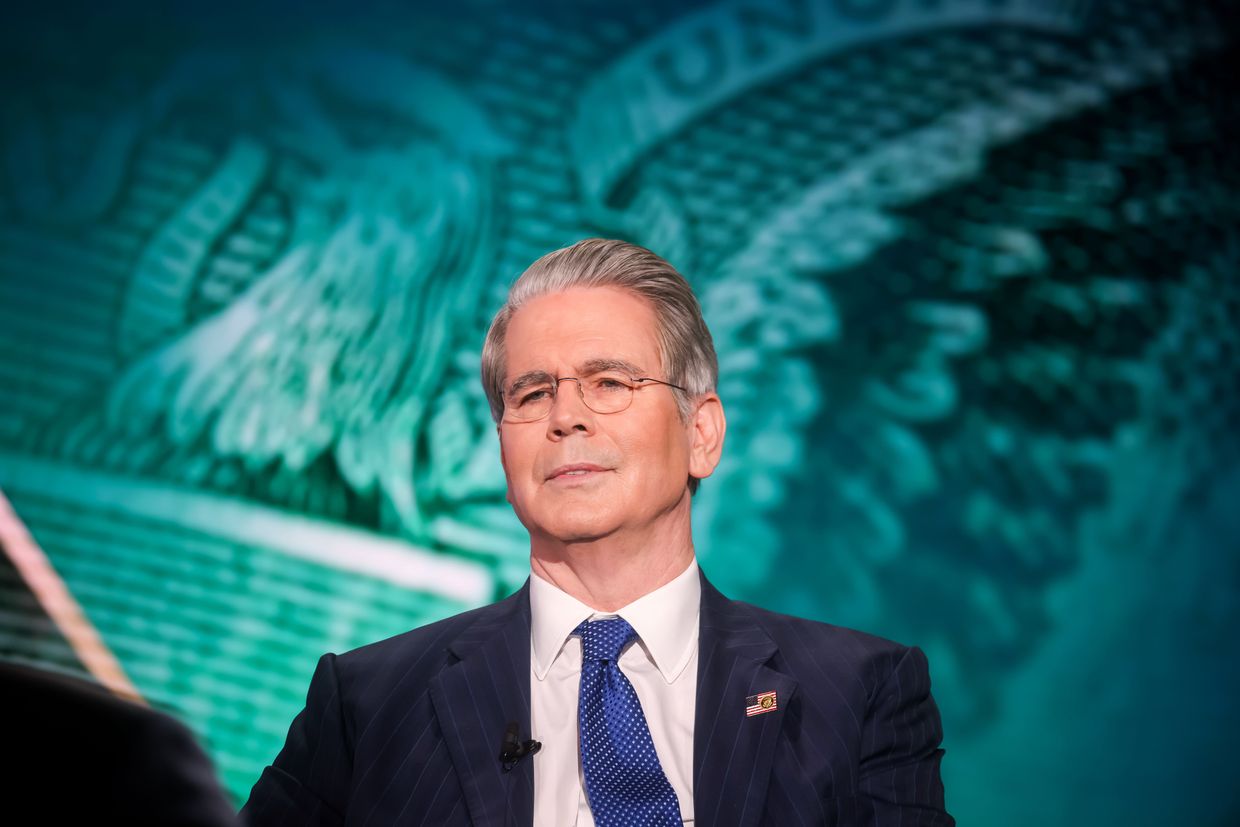

Amid Washington’s oscillating policy, EU sanctions chief David O'Sullivan warned of disunity on the sanctions front, German media Suddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) reported on May 27. Although even if the U.S. doesn’t end up imposing new sanctions, its current ones should remain in place, Vlasiuk said.

Fortunately for Ukraine, the EU is much more definitive on its sanctions policy. Brussels believes they are working and threatened “massive” sanctions if Russia rejects ceasefire proposals, which Moscow has so far.

“We are continuing to work on a new package of sanctions, precisely because that seems to be the only language that is understood by President Putin,” European Commission Chief Spokesperson Paula Pinho told the Kyiv Independent.

The 18th package will be ready “as soon as possible,” Anita Hipper, European Commission Foreign Affairs Spokesperson, said at a press briefing on May 22. It could take time, however, to get signed off by the EU’s problem child, Hungary, which has slowed down previous sanction efforts.

Details on the package have not yet been announced. But Hipper said the now destroyed Nord Stream pipelines connecting Europe and Russia would be included, likely to prevent their resurrection, as well as shadow fleet vessels, and crude oil.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on May 16 that Russia’s banking sector would also be included, with potentially 20 more banks disconnected from SWIFT. The EU may also propose lowering the oil price cap from $60 to $45 to further hit Russia’s energy sector.

Some are sceptical that the EU will actually deliver the blow that is really needed. “The problem is that Europe has continuously overpromised and under-delivered,” said Keatinge.

If Brussels is serious, then sanctions really need to tighten up the loopholes, said Vlasiuk. This means not just lowering the oil price cap but also sanctioning shadow fleet captains, prohibiting all maritime services for Russian oil exports, and a total ban on Russian LNG imports to Europe, which hit record levels last year, he said.

Europe should also continue to disconnect the remaining Russian banks from SWIFT, Vlasiuk said. Russia uses cryptocurrencies and third countries' financial systems to circumvent sanctions, and these should be cracked down on too, he added.

There are also raw material imports that Europe could go after to stop them from getting to Russia’s military sector. Ukraine has identified materials such as titanium, antimony, beryllium, lithium, and carbon fiber as potential targets.

“The Russian military defense sector is also very dependent not just on the microelectronics and cutting-edge technologies but also on selected raw materials and critical minerals,” Vlasiuk said.

“Sanctions work and we just need more,” he added.

Alex Cadier contributed reporting to this story.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Dominic Culverwell, thanks for reading this story. Sanctions are a topic many find difficult to wrap their head around, and I hope this story helped you understand their impact. It's important to us that our readers are as informed as possible. To help keep our stories accessible to all, please consider becoming part of our community for just $5 a month. We are so close to our goal of 20,000 members! Sign up here.

US blocks G7 push to tighten Russian oil price cap, Financial Times reports

The proposal was dropped after U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent reportedly declined to support it.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Ukraine Business Roundup

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  1 day ago

5

1 day ago

5

Comments