Around the world, abducting a child is a serious crime punishable by years behind bars.

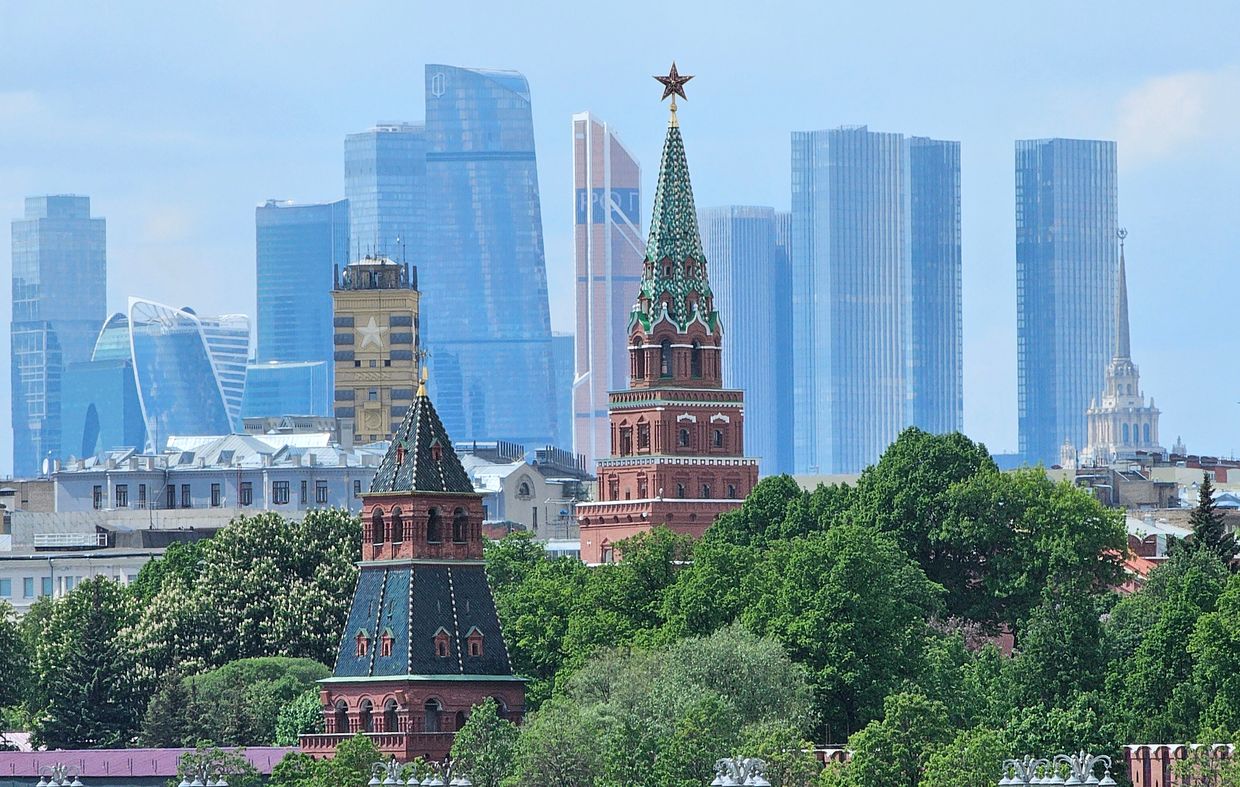

But when the kidnapper is Russia, justice remains a distant hope. So does the child’s return home.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine has identified over 19,500 children who have been forcibly deported to Russia, Belarus, or occupied territories. So far, only 1,300 of them have been safely brought back.

During their time in Russia, the children are placed in Russian families or camps, often undergo military training, and are subjected to intense propaganda designed to erase their Ukrainian identity.

Those who have returned report being punished for speaking Ukrainian and told that their homeland no longer wants them.

That constitutes a “calculated strategy” aimed at “completely severing their connection to Ukraine,” says Daria Zarivna, director of the Bring Kids Back UA, an initiative launched by President Volodymyr Zelensky to coordinate the return of abducted children. Zarivna is also an advisor to Zelensky’s chief of staff, Andriy Yermak.

For Ukraine, returning all these children is a key condition for any future peace agreement with Russia.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has also taken up the matter. In March 2023, it issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Children's Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova over their involvement in abductions.

But with no access to the children and little ability to determine their current locations, Ukraine has struggled to bring them home. It now largely depends on its international allies to facilitate their return.

In the meantime, Russia’s military offensive continues — as does its kidnapping of children.

Negotiations ongoing

Since U.S. President Donald Trump returned to office in January, continued U.S. support for Ukraine has repeatedly come under question. Trump himself has even suggested Ukraine started the war with Russia.

Despite that, experts say the U.S. remains committed to bringing Ukrainian children home.

On March 11, Ukraine raised the issue in Saudi Arabia during talks with the U.S. The meeting also included discussions of potential "territorial concessions" as part of a peace agreement between Kyiv and Moscow.

Despite the White House’s push to rapidly end the war, Zarivna says the humanitarian component was treated as a “crucial element" in the talks.

"We all agreed that it should never be excluded [from the agenda]," she told the Kyiv Independent.

Trump and Zelensky also discussed the abductions during their March 19 phone call. Trump promised "to work closely with both parties to help make sure those children were returned home," the White House said.

"Children should not be treated as bargaining chips. That goes against humanity."

Mike Walz, then the U.S. national security advisor, said in March that returning the children was among several "confidence-building measures" that were under discussion.

Zarivna emphasizes that the goal is to make the issue "depoliticized," meaning the children should not be exchanged with Ukraine in return for "nuclear power plants or territory."

"Doing so would only incentivize Russia to abduct even more children," she explains. "The children must be returned unconditionally, in accordance with international humanitarian law."

Former Children’s Rights Commissioner Mykola Kuleba echoes her point. He now heads Save Ukraine, a charity that rescues children deported to Russia.

"Children should not be treated as bargaining chips," Kuleba says. "That goes against humanity."

Kateryna Rashevska, legal advisor at the Regional Center for Human Rights, says this issue “radically changes” how Ukrainians should view peace talks with Russia.

“How can we believe any promise from Russia, even one not to invade us again, if it won't return the children it abducted?” she asked. “If Russia can't follow through on obligations it already agreed to long ago, including those under the law of Geneva and the Hague, why should we trust it with new commitments?"

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a Ukrainian official familiar with the matter told the Kyiv Independent that Trump aimed to achieve a “victory” in Ukraine to mark his first 100 days in office. It could potentially involve a ceasefire and the return of some civilians and children from Russia, but it has yet to materialize.

Kuleba believes that Trump could play a key role in returning the children. That might also help the government uncover crucial details about them and establish a mechanism for their rescue.

"In this way, we would establish the full scale of the catastrophe, identify all the affected children, both in Ukraine and in Belarus, and then we could help them," he suggests.

The Ukrainian official familiar with the matter says that U.S. negotiations with Russia about returning the children were still ongoing.

What happens next largely hinges on the pressure the U.S. and its allies can exert on Russia.

So far, however, Russia has shown no signs of de-escalating its military offensive. And it continues to illegally deport Ukrainian children, despite international pressure.

Training a new army

While Ukraine has identified 19,546 abducted children, the actual number may be much higher. Russia claims to have brought over 700,000 children to its territory since Feb. 24, 2022.

Measuring that number has only grown more difficult. After the ICC issued arrest warrants for Putin and Lvova-Belova, Russia halted all public reporting on the number of deported Ukrainian children.

Abductions can also be concealed behind more benign-sounding activities: vacations, education, or medical treatment.

For example, on March 19, Yevhen Balytskyi, head of the Russian-occupied part of Zaporizhia Oblast, announced that his administration would use funding from the Russian Education Ministry to relocate 70 children to a government-run summer camp in occupied Crimea. He claimed the move would help the children "rest and recover" after living near the front line – a common pretext for deportation.

Identifying and tracking abducted Ukrainian children is also challenging because Moscow deliberately changes their names, provides them with new documents, and disperses them throughout its vast territory.

A study by the Yale School of Public Health found that Russia has implemented a "systematic, intentional, and widespread" program of forced adoption and Russification of deported Ukrainian children. The researchers also found that Russian child placement databases have falsely registered these children as born in Russia.

One of the most striking cases occurred in 2023 when Russian lawmaker Sergei Mironov and his wife adopted a 10-month-old Ukrainian girl, Marharyta Prokopenko, who had been forcibly taken from an orphanage in the then-occupied Kherson. Her place of birth was changed to Russia, and she was given Russian citizenship.

According to Human Rights Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets, Marharyta Prokopenko "became Marina Mironova." Rashevska says that, now, the only way to prove the girl's identity is through a DNA test, which is impossible while she remains in Russia.

Abducted children are also regularly subjected to military-style reeducation programs aimed at not only erasing their Ukrainian identity but also preparing them for future service in the Russian military.

Rashevska says that these militarization efforts extend to both abducted children and the 1.6 million kids living in areas Russia has occupied.

"This means they are being militarized, re-educated, and Russified, with Russian citizenship being forced upon them,” she says. This group of children must also be (discussed during) negotiations, with guarantees that they will be treated as Ukrainians, she adds.

According to Rashevska, Russia's militarization of children is evident in the expanding reach of Yunarmiya (“Young Army”), a state-funded organization that teaches children military skills and fosters loyalty to the Kremlin.

Through presidential decree, Putin has also created the Warrior Center, which systematically prepares kids for service in the Russian military. Previously, there was one center in each occupied region except for Zaporizhia Oblast. Recently, however, Russia opened a new center in Mariupol, the second in the occupied Donetsk Oblast.

Rashevska expects the number of centers to grow.

"This way, Russia can rapidly achieve its goal of strengthening its mobilization reserve and military potential," she says.

Kuleba warns that if these children aren't brought back soon, they risk becoming part of Russia's war machine in future conflicts against Ukraine and the West.

"Through militarizing and brainwashing children, Russia could easily achieve an army of three million within five years," he says.

Note from the author:

Hi! Daria Shulzhenko here. I wrote this piece for you. Since the first day of Russia's all-out war, I have been working almost non-stop to tell the stories of those affected by Russia’s brutal aggression. By telling all those painful stories, we are helping to keep the world informed about the reality of Russia’s war against Ukraine. By becoming the Kyiv Independent's member, you can help us continue telling the world the truth about this war.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  6 hours ago

4

6 hours ago

4

Comments