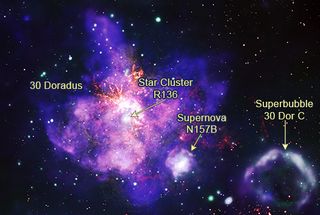

The petals of a cosmic Valentine's Day flower are unfurled in this image taken by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, revealing the most detailed X-ray image ever of the great star-forming nebula 30 Doradus in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

The four blue petals depict hot gas that's been energized by winds of radiation coming from nascent hot, young stars — as well as by these stars' eventual death cries rooted in the supernova explosions that mark the ends of their lives a few million years later.

Though 30 Doradus is ostensibly a star-forming region, it captures the entire life cycle of the most massive stars that live relatively short lives. In a way, these stars' cradles are also their graves. To emphasize the point, the most recent supernova to be visible to the naked eye, SN 1987A, exploded on the outskirts of 30 Doradus. And from the ashes of this and other dead stars, the beautiful cosmic flower has grown.

The X-ray emission from Chandra is presented here in blue and green. That's false color, of course — a representation of X-rays that we cannot otherwise see with our eyes. It's also the deepest-ever X-ray observation of 30 Doradus — Chandra's previous effort amounted to about 1.3 days' worth of exposures, whereas this new image accounts for 23 days of observations. Among the diffuse gas are 3,615 discrete X-ray sources, ranging from supernova remnants, compact binaries featuring neutron stars or stellar-mass black holes, X-ray pulsars, infant T Tauri stars and massive stars in binary systems. In fact, the exposure time was so long that Chandra could see some of these X-ray sources changing over time, brought about by phenomena such as the orbital mechanics of binary systems.

Thrown in for good measure is radio data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile that shows tendrils of dust depicted here in orange (again, false color) and Hubble Space Telescope optical data in yellow. Hubble has imaged 30 Doradus many times during its 35 years in space; the region is also known as the Tarantula Nebula because of its arachnid-like appearance in visible light.

The Tarantula spins its web in the Large Magellanic Cloud, which is a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way, 160,000 light-years from us. The nebula is huge, spanning 650 light-years in diameter. It's one of the most intense star-forming regions around, and in fact the largest in the Local Group of galaxies, which include the Andromeda and Triangulum spiral galaxies. It has been able to grow so huge because, unlike those spiral galaxies, where the differential rotation of the galactic disk creates sheer forces that rip gas clouds apart if they reach a certain size, the Large Magellanic Cloud doesn't have the same kind of differential rotation where some parts rotate faster than others.And fittingly for the largest star-forming region, it produces the most massive stars too.

Inside 30 Doradus is a giant, young star cluster called NGC 2070, and at the heart of that cluster is a dense concentration of stars — a cluster within a cluster, if you will — called R136. At the core of R136 lies the most massive star known in the universe, called R136a1. It is a Wolf–Rayet star, which is a type of temperamental massive star that is highly unstable and sheds its skin in violent pulsations. Its current mass is about 200 times the mass of our sun, but when it formed just over a million years ago, it had a mass about 325 times greater than our sun, and has expelled the difference in mass over its lifetime.

If 30 Doradus is a flower, then the expanding debris of supernova explosions within it carry the flower's pollen. Stars are element factories, fusing increasingly heavy elements in their central nuclear reactors, and producing even more precious metals in the ferocity of their supernova explosions. The debris from these stellar conflagrations is carried far and wide across space, germinating new sites of star and planet formation.

If you want to learn more about how this image was created, and what science it can teach us, you can read the paper about these results that was published in July 2024 in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments