Editor’s note: Due to the security protocols of the unit featured in this story, the Ukrainian soldiers are identified by first name only.

Russia’s air strikes on Ukraine have become far more deadly in recent months.

Part of the uptick is due to limited air defense to bring down ballistic missiles. But Russia’s preferred deep-strike weapon — the Shahed drone — has gotten some major upgrades since the start of the year, including jet engines and Starlink satellite attachments, putting pressure on Ukraine’s already strained air defense.

The Iranian-designed Shaheds that Russia now manufactures itself have been an ever-present force in Russian air assaults on Ukraine since the fall of 2022. Long-range, high-flying, and cheap — flocks of Shaheds have become a default deep-strike weapon for Moscow.

Inbound Shahed swarms have become increasingly unpredictable and deadly in recent months, Oleksiy, the commander of a mobile air defense unit that for the past two years has guarded the northwest of Kyiv from these drones, told the Kyiv Independent. Russia has been sending them in larger swarms and outfitting them with jet engines, complicating the task facing air defense across the country.

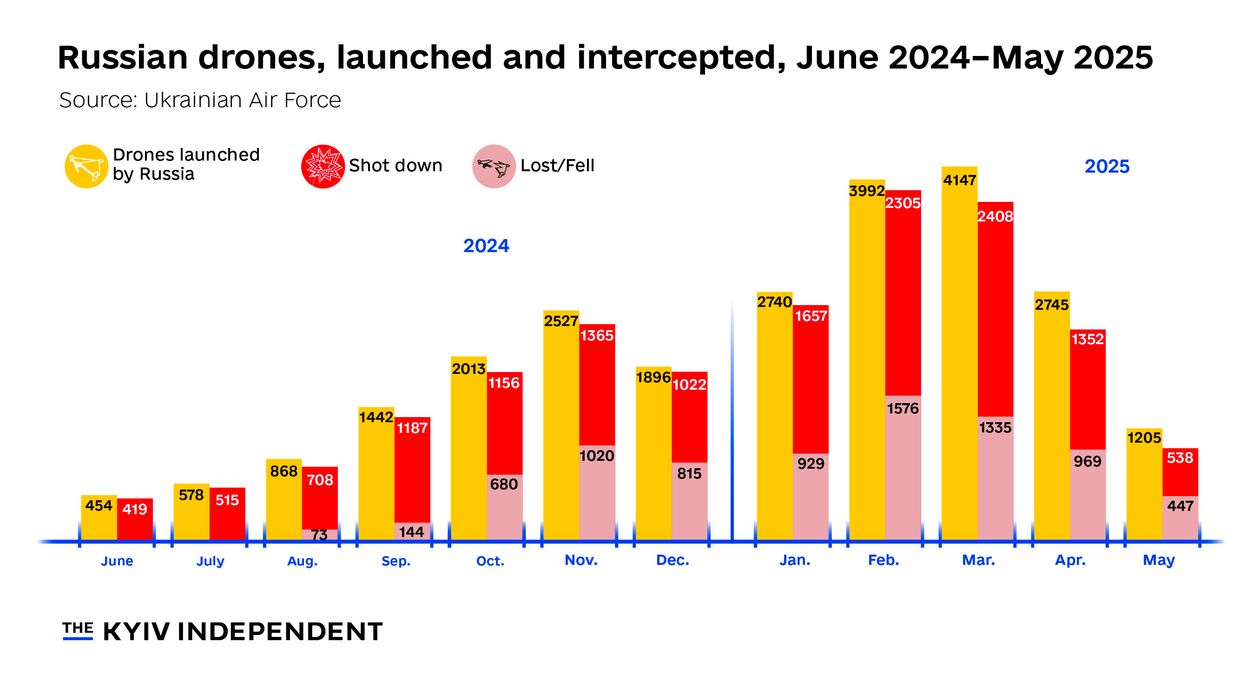

Numbers scraped from the Ukrainian Air Force’s reports on Shaheds incoming, lost, and shot down also show a major uptick in their effectiveness, even as the total number of Shaheds Russia sends is on the decline. One hundred and eleven made it through in February, compared to 404 in March and 424 in April. Meanwhile, the number of Shaheds that the Air Force reported as launched dropped by about a third between March and April.

The increasing effectiveness of Shaheds is largely thanks to the new jet engines, which allow the drones to fly faster, carry bigger bombs, and maintain higher altitudes.

Oleksiy says most of those jet engine drones travel between 380 and 400 kilometers an hour. The team clocked their record of a Shahed traveling at 477 kilometers per hour in the latter half of March, which they show off on a screenshot from the radar-based mobile application that all Ukrainian air defense units share. A year before, the max speed was in the neighborhood of 200 kilometers per hour.

Similarly, the maximum payload that these Shaheds carry has tripled from about 30 kilograms to 90 kilograms. That remains a far cry from the 450 kilograms a cruise missile like the Kh-101 can carry, but Russia fields far more Shaheds.

The new engines also bring these Shaheds higher in the sky, as needed, reaching a ceiling of around 2 kilometers. The vertical range of a Browning machine gun like the one that Oleksiy shoots is, he says, more like 1,800 meters. Shoulder-mounted surface-to-air missiles like the Soviet Igla and American Stingers work at higher ranges, but are in shorter supply.

Russia does, however, face some limits in adding jet engines to Shaheds. They are more expensive than the two-stroke piston engines — replicas of the U.S.-made MD550 — that Shaheds started out the war with. Russia often has to import jet engine technology, sometimes with Western components delivered through third parties to get around sanctions.

About half of the Shaheds that radar picks up coming into Ukraine are “dummy” drones — no warheads, and so generally cheaper while distracting enemy fire. Many of those show up in the data as “Lost/Fell.”

The actual material of a typical Shahed is remarkably flimsy relative to what one would imagine of a weapon of war. Water condenses with the cold further up in the atmosphere, which has typically weakened the Shahed’s structure. The team says the Shaheds are getting a new coating that makes them more resistant to the moisture they run into higher up.

“At lower altitudes, we have something like five or six seconds to work, when we need to find, target, and destroy them.”

Russia also frequently flies Shaheds low, which is dangerous because, while are easier to hit, they are harder to detect. Land-based radar signals, the core of Ukrainian identification, don’t return good location data on Shaheds flying below the horizon.

Indeed, the team's radars picked up the 477-kilometer-per-hour Shahed at 300 meters above ground. Some glide as low as 100 meters above ground, giving satellites and mobile teams a tiny window of time in which to spot and shoot them down.

“At lower altitudes, we have something like five or six seconds to work, when we need to find, target, and destroy them,” said Oleksiy. More over-the-horizon radar would, he said, go a long way for groups like theirs.

The Shaheds have historically also run fairly robotically along pre-planned flight paths. Now, some are avoiding spotlights like the one that one team member of the unit, Svita, uses to spot them in the sky. Light avoidance could be new programming added to Shahed visual guidance, Oleksiy explained.

Their dependence on visual guidance, however, meant that Shaheds clung to familiar routes for most of the time they’ve been flying over Ukraine. “They used to lay out a route for the Shahed, and it would go right along the route. It was simple to destroy them. At the moment, they react to light; that is, if you turn on the flashlights, they start making maneuvers,” said Oleksiy.

Those on the way to Kyiv often stuck to the Dnipro River or the sleek new Odesan Highway that is the main thoroughfare southward to the Black Sea and the titular town, Ukraine’s second-largest. That also seems to have changed recently.

“A few of them are actively guided, that is, they are being steered online. They film our positions, see us, and record us, so later they try to fly around us,” said Oleksiy.

The coordinator for a number of these regional mobile defense units specified to the Kyiv Independent that some of these Shaheds are also flying with Starlink Terminals that keep them connected to pilots in Russia in flight.

Updated Ukrainian Comms

Ukraine’s mobile defense teams have also gotten far better at shooting down drones over the past two years. Oleksiy told the Kyiv Independent that his team managed to shoot down six Shaheds flying through their little quadrant of the Ukrainian sky during March.

The team’s central tool is a truck-mounted Browning machine gun. A major upgrade over the past two years has been the distribution of thermal vision across the front line, which can work in times when Svita’s spotlight cannot.

The actual hardware many use is not that complicated, certainly not compared to what air defense groups aiming for cruise or ballistic missiles use. But these air defense teams have to work in close coordination across the entire country because Russia combines its attacks of drones and missiles and feint take-offs and launches of various MiG airplanes from airfields within range of Ukraine.

But Ukraine’s air defense communications are leaps and bounds ahead of where they were in 2022. Applications like Visage — developed just before the full-scale invasion — have radically improved their ability to track incoming air attacks. They are also integrated with the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ ubiquitous Delta mapping and communications application.

Even thermal vision targeting and shooting are linked via a tablet application. These days, mobile air groups around the country effectively share screens on the application live.

Oleksiy shows off a grayscale but high-resolution hit from another team in Chernihiv Oblast, firing on a Shahed that erupts into red flames.

“Looks good, right?” Oleksiy chuckled. “Like something out of the movies.”

KI Insights analyst Mykolaj Suchy contributed data analysis to this article.

Hi, this is Kollen, the author of this story — thank you for reading. The Kyiv Independent doesn’t have a wealthy owner or a paywall. Instead, we rely on readers like you to keep our journalism funded. We’re now aiming to grow our community to 20,000 members — if you liked this article, consider joining our community today.

Ukrainian drones strike Russian ammunition depot in occupied Crimea, source says

The depot, located near a key highway between Simferopol and Alushta, reportedly housed military equipment, ammunition, and fuel storage facilities. Local residents reportedly described thick smoke over the military compound.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  5 hours ago

2

5 hours ago

2

Comments