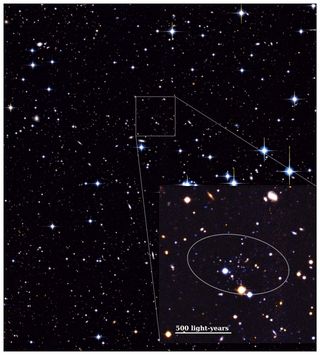

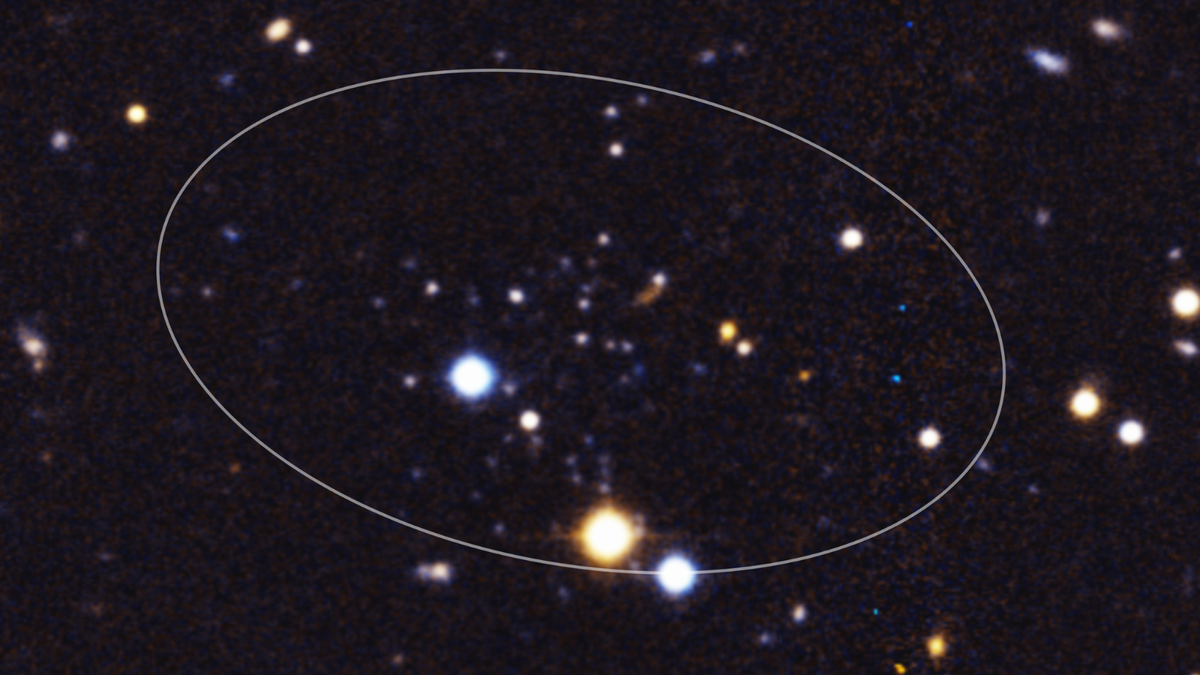

Astronomers have discovered a collection of tiny galaxies located roughly 3 million light-years away that includes the smallest and faintest galaxy ever seen.

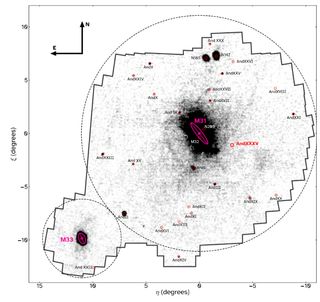

This galaxy, designated Andromeda XXXV, and its compatriots orbiting our neighbor galaxy, Andromeda, could change how we think about cosmic evolution.

That's because dwarf galaxies this small should have been destroyed in the hotter and denser conditions of the early universe. Yet somehow, this tiny galaxy survived without being fried.

"These are fully functional galaxies, but they're about a millionth of the size of the Milky Way," team member and University of Michigan professor Eric Bell said in a statement. "It's like having a perfectly functional human being that's the size of a grain of rice."

Meet Andromeda XXXV

Dwarf galaxies themselves are nothing new to scientists. Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is orbited by dozens of these satellite galaxies caught in the grip of its more immense galaxies.

There is, however, a great deal about dwarf galaxies that scientists don't know. This is because, being smaller, they are much dimmer than major galaxies, making them harder to spot and tougher to study at large distances.

While astronomers have been able to determine many dwarf galaxies in orbit around the Milky Way, identifying dwarf galaxies around our bright galactic neighbors has been incredibly difficult. This means that the dwarf galaxies of the Milky Way have been our only source of information about small satellite galaxies.

This task is somewhat less challenging around the closest major galaxy to the Milky Way, Andromeda. Other dwarf galaxies have been spotted around Andromeda before, but these have been large and bright, thus simply confirming the information that astronomers had gathered about dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way.

To discover these paradigm-shifting smaller and dimmer dwarf galaxies, team leader Marcos Arias, an astronomer at the University of Michigan, and his colleagues scoured various massive astronomical datasets. The team was also able to obtain time with the Hubble Space Telescope to aid their search.

This revealed that not only is Andromeda XXXV a satellite galaxy, but it is also small enough to change theories of how galaxies evolve.

"It was really surprising," Bell said. "It's the faintest thing you find around, so it's just kind of a neat system. But it's also unexpected in a lot of different ways."

A cosmic murder mystery

One of the key aspects of galactic evolution is how long their star-forming periods last. This seemed to be the main difference between the Milky Way's dwarf galaxies and the smaller satellite galaxies of Andromeda.

"Most of the Milky Way satellites have very ancient star populations. They stopped forming stars about 10 billion years ago," Arias explained. "What we're seeing is that similar satellites in Andromeda can form stars up to a few billion years ago — around 6 billion years."

Star formation requires a steady supply of gas and dust to collapse and birth stellar bodies. When that gas is gone, star formation halts, and the galaxy "dies."

Thus, Bell described the situation around these small galaxies as a "murder mystery." Did star formation end when dwarf galaxies' gas supplies petered out on their own, or when these gases were gravitationally stripped away by a large galactic host?

In the case of the Milky Way, it appears that the gas for star formation petered out on its own; however, for the smaller galaxies around Andromeda, it appears they were "killed" by their parent galaxy.

"It's a little dark, but it's either did they fall or did they get pushed? These galaxies appear to have been pushed," Bell said. "With that, we've learned something qualitatively new about galaxy formation from them."

What is even more curious is the extended period of star formation experienced by Andromeda XXXV. To understand why, it is necessary to travel back in time to the the birth of the first galaxies.

Why isn't Andromeda XXXV a 'deep fried' galaxy?

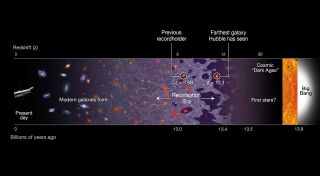

The earliest epoch of the universe was marked by incredibly hot and dense conditions. This inflationary period, begun by the Big Bang, continued, and the universe dispersed and cooled. This allowed the first atoms of hydrogen to take shape, birthing the first stars, which gathered in the first galaxies.

These stars and galaxies blasted out energy as did the first feeding black holes reheating the cosmos. This signaled the death of very small galaxies, and scientists theorize this heat "cooked off" the gas needed for star formation in such collections of stars.

Yet, somehow, Andromeda XXXV survived!

"We thought they were basically all going to be fried because the entire universe turned into a vat of boiling oil," Bell said. "We thought that it would completely lose its gas, but apparently that doesn't happen, because this thing is about 20,000 solar masses and yet it was forming stars just fine for a few extra billion years."

Just how Andromeda XXXV resisted being fried is still a mystery.

"I don't have an answer," Bell said. "It is also still true that the universe did heat up; we're just learning the consequences are more complicated than we thought."

NASA and other space agencies are planning missions that could discover further dwarf galaxies around other large galaxies and help solve this mystery. But there's a good chance that the solution will open up new questions just as the discovery of Andromeda XXXV has.

"We still have a lot to discover," Arias said. "There are so many things that we still need to learn — even about what's near to us — in terms of galaxy formation, evolution, and structure before we can reverse engineer the history of the universe and understand how we came to be where we are today."

The team's research was published on Tuesday (March 11) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments