Dec 8, 2024 | For Zeenat, it may have been the call of the wild, some primal instinct that urged her to move. The three-year-old tigress was supposed to stay within the confines of Odisha’s Similipal Tiger Reserve, where she had been translocated from Maharashtra’s Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve. But Zeenat knows no manmade borders. She gave in to the wild wanderlust and sets out from the reserve, traversing Odisha, Jharkhand and Bengal, travelling more than 300km and setting off a flurry of activity among forest officials. She is finally captured at a village in Bengal’s Bankura on Dec 29.

Jan 12, 2025 | A male tiger in its prime enters Bengal from Purulia, gets clicked in a camera trap, giving the district its first ever recorded evidence of a tiger. As the big cat keeps wandering between Bengal and Jharkhand, the tiger cell at National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) confirms that it was first photographed in a trap camera in Chhattisgarh’s Balrampur forest division in March 2024, then in Jharkhand’s Palamau Tiger Reserve in May-June and later in Bengal’s Purulia and Jhargram in Jan 2025.

Stripes & Strays

India’s animal translocation efforts have come under serious scrutiny. The ambitious cheetah project in MP’s Kuno National Park has already courted controversy, having recorded numerous deaths since the first cheetah was released there from Africa in 2022. Even intra-country efforts are not going as planned, as evidenced from Zeenat’s travels. Another tigress — Yamuna — procured from Tadoba is also not settling down in Similipal, even as Bengal grapples with a tiger for the second time in three weeks. This has raised serious doubts on the practice of ‘forced’ redistribution of big cats from tiger-rich states to depleted habitats.

India has seen a significant ‘unplanned’ movement of big cats in recent weeks, of them either straying into human settlements, or moving out of designated zones, reminding wildlife authorities of challenges in tiger conservation efforts. Recently, a tiger dispersed from Sariska Tiger Reserve and strayed into human habitation in Rajasthan’s Alwar, until it had to be darted and brought back to its habitat.

Green Passages

Managing translocated animals and ensuring survival of their cubs in the wild is a bit tricky, given the risks involved, says

Subharanjan Sen

, MP’s chief wildlife warden. “In Kuno, we initially brought eight cheetahs. Later on, 12 were released in phases. The cheetah was extinct in India, and we brought the cubs from Namibia. I will not call the project a failure, but eight adult cheetahs have died. The population is now 24. Out of 17 cubs, 12 have survived.”

Even though this is a reminder of the complex dynamics of forced redistribution, National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) is pushing forward with its ambitious tiger recovery programme. A new proposal aims to relocate 15

tigers

from MP to three states: Odisha, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh.

Past experiences raise concerns about the success of such programmes, though NTCA member secretary Gobind Sagar Bhardwaj says comprehensive management efforts would be taken before executing relocation of tigers in Similipal, especially after a poaching of a melanistic tiger.

What happens to Zeenat will decide the fate of 15 tigers in India

Experts are wary, as state govts, in their eagerness to showcase conservation success, often overlook critical scientific protocol. “Translocation has become more about political image-building than scientific wildlife management,” says wildlife conservationist Biswajit Mohanty.

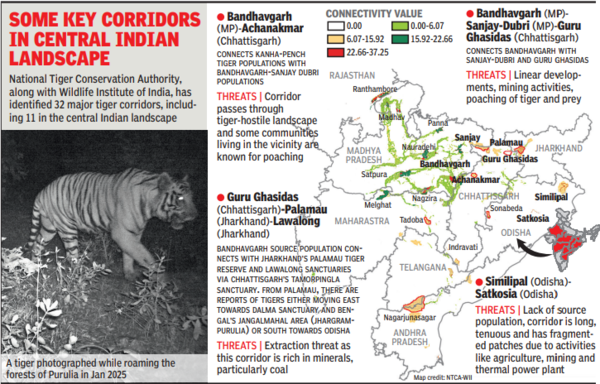

Experts say the recent movement of wandering tigers, particularly in east-central India (covering Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Bengal), points to the importance of preserving and maintaining ‘wildlife corridors’ — designated areas that connects wildlife populations that have been separated by human activity.

These corridors, many feel, would do naturally what forced translocations are failing to achieve: long-term survival of wildlife, guard against localised extinctions and ensure exchange of gene flow, which helps in population diversity. In other words, let Mother Nature have her say.

“If movement corridors are restored, in the long run, they will naturally ensure tiger dispersal from one landscape to another,” says scientist and conservationist

Y V Jhala

, who recently retired as dean of Wildlife Institute of India (WII) and was in charge of the initiative to reintroduce the cheetah in India. “This, coupled with good management practices and protection measures in tiger landscapes, will lead to less dependency on relocation projects such as those for tigers.”

Corridor Trails

But chances of restoring the corridors are very little, given there’s so much fragmentation, says K Ramesh, a senior scientist and professor with WII. “Many corridors have gone beyond restoration because of agriculture and developmental activity,” he adds.

There is, however, still some evidence that some wildlife trails still exist. In March 2023, a dispersing tiger was caught in a camera trap in Odisha’s Bonai division. NTCA tiger cell sources said this big cat was clicked in a trap camera in MP’s Sanjay National Park when it was a cub. It was also later clicked in Jharkhand’s Palamau Tiger Reserve. But unlike the ‘Purulia tiger’, which headed east from Palamau to enter Bengal, this tiger headed southwards to reach Odisha, pointing towards a still-functional corridor on the landscape.

Between 2010 and 2022, the tiger population in India has grown from 1,700+ to 3,600+, presenting a new challenge, despite this success: long-distance migration of big cats, particularly males, from reserves with surplus populations.

MP and Maharashtra, two of the best performing states in terms of tiger conservation, frequently witness migrations eastwards towards the forests of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Telangana and Bengal.

But here, most areas neither have enough prey nor female tigers, two things that dispersing male tigers look for.

“At Palamau, we have been regularly getting pictures of tigers since 2022, but all are males,” says

Kumar Ashuthosh

, who recently retired as field director, Palamau Tiger Reserve. “It is the dearth of female tigers, perhaps, that is not allowing more males to settle there. Some of them often vanish after wandering into the reserve. There were plans to write to NTCA to get two females under a relocation programme, on the lines of Similipal.”

But such translocation projects, too, present certain challenges.

Early Hiccups

Rajasthan’s Sariska and MP’s

Panna

were the first two parks to show the way in terms of tiger relocation in India. But a similar move — the first such inter-state project in India — failed, when two big cats from MP’s Bandhavgarh and

Kanha

couldn’t make Odisha’s Satkosia their home. While the male tiger fell prey to poachers, the female (Sundari) had to be sent back to Kanha and then to a zoo after being tagged ‘man-eater’.

On the Panna model, a senior MP forester said that by 2009, Panna National Park became the second tiger reserve in India after Sariska to lose all its tigers. But Panna has successfully reintroduced tigers into the park’s natural habitats, resulting in close to 80 tigers, including cubs, thriving within its more than 500sq km boundaries.

Despite starting early, Sariska, where the current tiger population is about 30, lags behind.

“Issues like village relocation and poaching threat continue to prevail,” a source says.

Taking lessons from Satkosia, authorities in north Bengal’s Buxa Tiger Reserve, where a similar plan is afoot, are treading cautiously. If all goes well, tigers may be brought either from Kaziranga or Orang, both in Assam, to Buxa, where camera traps had captured a tiger in Dec 2021 after four decades — again underscoring the importance of corridors between forests of Bhutan, Assam and N Bengal. Plans are on to shift two villages from the core area.

In Palamu, NTCA had sent a proposal for tiger relocation to the back burner because of two villages with over 200 families inside the core area. According to RameshF, the Palamau habitat is still good and that tigers will make a comeback once the prey numbers rebound.

The Road Ahead

The success of tiger relocation plan depends on how much connected the forest department is with local communities, where newly dispersed tigers will invariably disperse, Sen says. “Satkosia did not have enough prey and a new tiger was introduced, leading to Sundari’s dispersal soon after release,” he explains.

Another thing to bear in mind is the peculiar challenges posed by new habitats. Though Similipal’s landscape is considered to be closely similar to central India’s in terms of flora and fauna, its high terrain and rocky hills are unique, absent in most tiger habitats in Maharashtra and MP. In Zeenat’s case, the Odisha forest department has it on record that the tigress got frightened by herds of elephants, which made it disperse too far.

Bhanumitra Acharya, a former honorary wildlife warden, says translocation efforts are jeopardised by hasty decisions, often for the sake of “image-building of the receiving state.”

With Zeenat’s fate now locked in a soft enclosure, it is not going to be easy for authorities to take a call on its re-release into the wild. Anup Nayak, former member secretary, NTCA, feels flawed selection of tigers for translocation — especially its age — is also crucial. “Tigers that are either too young or too old often struggle to adapt to new environments. Also, tigers that have grown up in areas with human presence pose risks in their new habitats,” he says.

Tigers are also exploratory creatures, and it’s natural for them to look for their own solitary space once shifted to a new habitat,” says Joydip Kundu, a conservation campaigner and founder of SHER (Society for Heritage & Ecological Researches). “Tigers always start exploring new landscapes, and this can land them in different sanctuaries at times. But it is their right to get corridors to move and forests rich with enough prey.”

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2

Comments