Long before he became a meme for slapping Chris Rock at the Oscars for a joke that seemed like a punchline for Big Pharma to sell some follicular solutions, Will Smith acted in some remarkable movies. One of the most moving was The Pursuit of Happyness, a fine film on paternal-filial relationships. In a rather dark moment, he wonders if Thomas Jefferson gaslit America by stating in the Declaration of Independence that every American would be endowed with certain rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He says in the movie: “And I remember thinking: how did he know to put the pursuit part in there? That maybe happiness is something that we can only pursue and maybe we can actually never have it. No matter what.”

It’s a sentiment that the World Happiness Report 2025 appears to agree with—at least for Indians, who have been ranked 126th among 143 countries, despite the fact that it’s a rising global power—one of the few, to borrow a line from the proverbial egg-faced Shashi Tharoor, whose leader can hug both the premiers of Ukraine and Russia.

Don't Let Somebody Tell You, You Can't Do Something - Pursuit Of Happiness #pursuitofhappyness

Through the WENA Looking Glass

But that’s hardly surprising, because it completely fits into the WENA idea of India. If one were to learn about India solely from Anglosphere coverage, one would assume that India was a genocidal hellhole where the living conditions were worse than sub-Saharan Africa.

The fact is that if irony could be measured, the World Happiness Report 2025 would be a more shoddily written Don Quixote. India is ranked 126th—below Qatar (23), Saudi Arabia (32), Libya (80), Venezuela (82), Uzbekistan (52), Rwanda (92), China (60), Iran (92), Bangladesh (101), Lebanon (104), Palestine (108), Pakistan (109), Ukraine (111), Iraq (113), Egypt (104), Ethiopia (115), Cameroon (118), the Democratic Republic of Congo (124), and Myanmar (125)—a list that includes war zones, authoritarian regimes, debt-ridden states, and nations facing civil unrest. Even if one were to accept that there are enough citizens of the world who prefer being a fed sparrow to a hungry songbird, even Pakistanis would be shocked to learn that they are ranked above India and would wonder if the only person surveyed for this poll was Osama Bin Laden.

The Numbers Don't Lie

So, before we get into the problem with the methodology, let’s do a simple headcount between India and Pakistan. Currently, India’s GDP is $3.7 trillion—the fifth largest in the world and the only one after the US to outstrip its former colonial rulers. Pakistan, meanwhile, is a $375 billion economy—not even 10% of India’s size. India’s digital economy is booming, startups are thriving, and infrastructure is expanding at a record pace. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s economy is lurching from one IMF bailout to another like a tippler looking for his next drink.

Pakistan is essentially running on loans. The country has over $125 billion in external debt, with crippling inflation and foreign reserves barely enough to cover a few weeks of imports. It defaulted on several payments before being saved by yet another IMF bailout. India, by contrast, is not only managing its debt prudently but has become a net lender to the IMF.

Coup Cabinets and Comic Timing

As for the contrasting militaries, there’s a delightful anecdote from 1957 recalled by Anvar Alikhan in a QZ piece titled Why India Has Never Seen a Military Dictatorship, where he draws parallels between the militaries of the two countries.

He writes: “A true story: In 1957, the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, visiting the office of General Thimayya, the Chief of the Army Staff, saw a steel cabinet behind his desk and asked the general what it contained. The general replied that the top drawer contained the nation’s defence plans. And the second drawer contained the confidential files of the nation’s top generals. And what about the third drawer, enquired Nehru. Ah, said the general with a straight face, the third drawer contains my secret plans for a military coup against you. Nehru laughed, but there was apparently a tinge of nervousness to his laughter.”

While the idea of a military coup in India remained a joke locked in a cabinet, in Pakistan, the military was so good at dealing with law and order and other issues that whenever martial law was declared, people would rejoice: “Pakistan mein ab toh mashallah ho gaya,” playing on the term martial law.

Theocracy vs Democracy

While India became a nuclear-armed democracy—warts and all—Pakistan devolved into a de facto military state whose generals always had more power than elected officials. Coups happened with the alacrity of Friday prayers. In fact, Imran Khan was propped up by the military to counter mainstream politicians, but the former World Cup winner soon became more powerful than his puppeteers intended. Yet, a country where the army decides your prime minister, your policies, and sometimes even your breakfast menu is apparently living its best life.

Yes, India’s secularism is under scrutiny and faces legitimate criticism. But it still remains a constitutionally enshrined, functioning democracy with an independent judiciary, regular elections, and a diverse press. Pakistan, in contrast, is a state founded on religious identity and has institutionalised discrimination against minorities. Ahmadiyyas can’t even call themselves Muslim, and Hindus are regularly persecuted. Minorities live under a blasphemy law that’s been used more as a weapon than a shield.

So, how exactly does a theocracy with enforced religious conformity and institutional bigotry outscore a pluralist democracy—even if imperfect?

Big Stage vs Bailouts

India is seen as a rising power on the global stage. It’s hosting G20 summits, mediating in global conflicts, and pushing for a multipolar world. Pakistan, meanwhile, is often the subject of IMF reports, FATF warnings, and UN human rights resolutions. India’s passport opens doors; Pakistan’s passport raises eyebrows.

In fact, the contrast between India and Pakistan can even be seen in both nations’ favourite pastimes: cricket. In recent years, much to the chagrin of English and Australian columnists, India has become the de facto Trump of world cricket—big enough to call the shots—so much so that when Pakistan finally got the chance to host a Champions Trophy, India refused to set foot. While the Pakistani team went out dismally in the group stage, India romped home to pick up the trophy without as much as breaking a sweat. To add insult to injury, India’s dominance meant that Pakistan (the hosts) had to travel to Dubai to play its match, and India reaching the final robbed Pakistan of the spectacle.

Wasim Akram Khuda Ka Khof Kare Tendulkar Aur Babar Ek Jese Nahi | Wasay Habib | Commentary Box

India’s changed standing on the global stage can be summarised by the contrasting online reaction to a tweet from an American commentator with a Ukraine flag (a marker of online inanity), which wondered why there was no outrage when Prime Minister Modi (like Zelenskyy) wasn’t dressed in a suit. Most commentators pointed out that Modi was dressed in traditional garb (a kurta pyjama and a jacket) as opposed to Zelenskyy’s cosplay sweatshirt and khakis. However, the real kicker was even white Americans—who often spend time mocking JD Vance’s wife—defended the Indian Prime Minister because he wasn’t in America asking for more funds and weapons.

The Metrics Mirage

The implication that India—a growing economy, a space-faring democracy, and a hub of innovation—is less “happy” than war-torn or economically collapsed nations raises serious questions about the methodology behind these rankings. The report relied heavily on subjective self-assessments, primarily via Gallup’s “Cantril Ladder,” where respondents rated their lives on a scale from 0 to 10. These were then modelled against six variables: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom, generosity, and perceptions of corruption. However, many of these variables were based more on perceptions than hard data. In societies where expectations are low, or media is tightly controlled, people often report higher satisfaction. In contrast, in dynamic democracies like India, rising aspirations, political noise, and media scrutiny tend to yield harsher self-assessments—even in the midst of tangible progress.

All of this brought renewed attention to the flaws of international perception-based indices—something Sanjeev Sanyal and Aanchal Arora had flagged in a 2022 working paper. They had offered a pointed critique of three influential global indices: Freedom in the World (by Freedom House), Democracy Index (by the Economist Intelligence Unit), and the V-Dem Indices (by the University of Gothenburg)—all of which had routinely rated India poorly.

Sanyal-Arora had argued that these indices were largely opinion-driven, relying on small, opaque pools of anonymous “experts” whose identities, qualifications, and nationalities were often undisclosed. Freedom House, for instance, used 25 subjective questions assessed by internal analysts and external advisers, but published no transparency on scoring mechanisms. The EIU claimed to use public opinion, yet India’s last World Values Survey input dated back to 2012—meaning more recent assessments were based almost entirely on expert opinion. V-Dem, meanwhile, used 473 variables, many of them highly subjective, including notions like “self-censorship” or “deliberative quality of governance.”

They also noted that many of the questions used were ill-suited for cross-country comparisons, such as “how pervasive is corruption?” or “to what extent is direct popular vote utilised?”—metrics that penalised democracies like India and the US for not holding national referendums, while awarding higher scores to one-party states like Cuba.

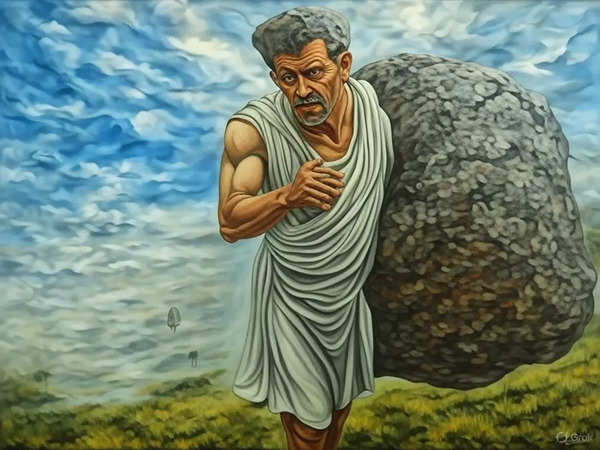

The Sisyphus Clause

India and Pakistan are on two different trajectories, and even the honest Pakistani knows that. If Albert Camus was right, then perhaps the secret to happiness lies not in prosperity, democracy, or purpose—but in the acceptance of futility, the repetition of struggle, and the knowledge that there is no divine reward at the summit.

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus describes a man condemned to eternally roll a boulder up a mountain, only for it to roll back down each time. It is an absurd fate, but in contemplating it—knowing it is his, accepting it as unchangeable—Sisyphus becomes, paradoxically, free. Camus writes: “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Perhaps this, then, explains Pakistan’s higher ranking in the World Happiness Report 2025. Perhaps Pakistan is the Sisyphus of South Asia. A nation locked in a cycle of economic collapse, military coups, IMF bailouts, energy shortages, and cricketing heartbreak, and yet—it smiles on the way back down the hill.

I said that the world is absurd, but I was too hasty. This world in itself is not reasonable, that is all that can be said. But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart. The absurd depends as much on man as on the world.

Albert Camus

Where India fights, debates, builds, reforms, and aspires—Pakistan accepts. It no longer expects the summit. Its happiness is not driven by achievement but by survival, not by growth but by repetition. Where India agonises over its democracy, Pakistan no longer pretends to have one. Where India chases global leadership, Pakistan is content negotiating its next loan. There is peace in low expectations, freedom in detachment. If happiness is the absence of disillusionment, then what better strategy than to stop being illusioned in the first place?

And so, while Indians grumble through traffic jams in growing cities, rage against corruption, or demand better governance, Pakistanis return to their rock each morning, lift it with muscle memory, and smile—because nothing else was promised. As Camus wrote: “Each atom of that stone... forms a world.”

Every bailout is a new beginning. Every coup, a cosmic reset. Every World Cup loss, a philosophical cleansing. They roll the rock. It rolls back. The absurd cycle is complete. Meanwhile, India is caught in its own existential spiral—still believing happiness is to be earned, still chasing Jefferson’s promise of “the pursuit”, still demanding meaning from its journey. But as Camus warns, meaning is a human construct. The world owes us none.

So maybe Pakistan is happier.

Not because it is richer, freer, safer, or better—

But because, like Sisyphus, it has made peace with the mountain.

And it no longer asks why.

.png)

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  7 hours ago

2

7 hours ago

2

Comments